|

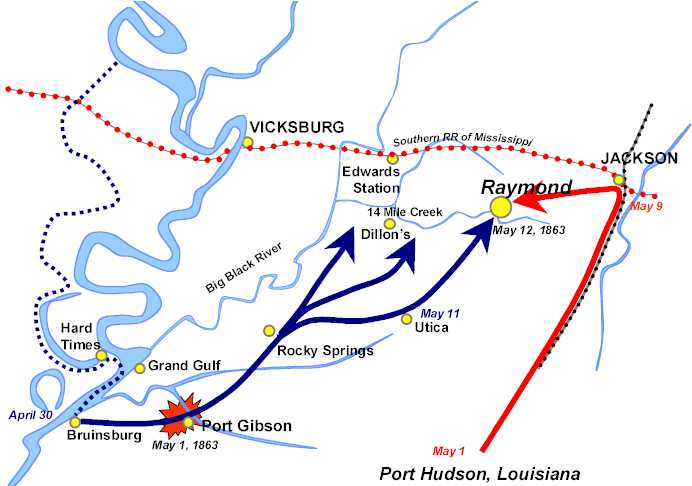

The Battle of Raymond By Parker Hills The Vicksburg Campaign has been called "the most brilliant campaign ever fought on American soil" by the United States Army in its "how to fight" manual, the 1986 version of its FM 100-5 Operations.1 Yet, this series of military operations is often overlooked by historians and Civil War aficionados alike, left in the shadows of famous Civil War battles such as Antietam and Gettysburg. Consequently, the battles of Major General Ulysses S. Grant's masterful offensive campaign are obscure and often misunderstood in their role as decisive moments in history. Not the least of these is the Battle of Raymond, Mississippi. After months of futile attempts to capture "Fortress Vicksburg," the mighty citadel that prevented almost virtual Union control of the Mississippi River, Grant moved his army south of the belligerent city in the spring of 1863 by trudging through the Louisiana swamplands west of the river. Because of Grant's ruses and raids, such as Sherman's well-executed diversion just north of Vicksburg and Grierson's famed cavalry jaunt through Mississippi, this monumental march went virtually unnoticed by the Confederate army commander, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton. Then Grant, with the help of the Union Navy, deftly transported his army, unopposed, across the murky Mississippi; ascended the 200-foot loess bluffs on the Mississippi side of the river; and tramped inland on April 30. On May 1, Grant's bluecoats defeated a much smaller makeshift Confederate force just west of Port Gibson, Mississippi, thus, securing Grant's lodgment on Mississippi soil just 26 miles south of Vicksburg. Pemberton's forces fell back towards Vicksburg in a defensive posture, expecting Grant to attack directly north in order to capture the "Gibraltar of the Confederacy." Grant, however, maintained the element of surprise by marching his army northeastward, using the Big Black River to protect his left flank. His preliminary target was a "decisive point" called the Southern Railroad of Mississippi. This railroad connected Vicksburg to Jackson, the state's capital, and from Jackson to points in all directions. Grant's plan was deceptively simple: cut Pemberton off before destroying him.

On the evening of May 11, Grant's forces were preparing to move to an east-west line that ran parallel to the railroad, and just a few miles south of it. Major General John A. McClernand's soldiers of the 13th Corps were about 15 miles west of Raymond, and Major General William T. Sherman's 15th Corps was on McClernand's right, about 11 miles west of Raymond. Major General James B. McPherson's 17th Corps was scheduled to complete the line by forming on Sherman's right at Raymond, but the setting sun found McPherson's men about nine miles southwest of Raymond on the Utica Road. The insufferably hot, dry weather and accompanying lack of water along McPherson's route had hindered the young general's rate of march. Grant established his headquarters with McClernand at the hamlet of Cayuga on May 11th, and dashed off a message to the lagging McPherson, who was camped at the Roach farm on the Utica Road. Grant directed McPherson to move his corps as quickly as possible to Raymond.2 Simultaneously, McClernand's and Sherman's corps were to move to the north and east to form the left and middle segment of a line roughly six miles south of, and parallel to, the railroad. McPherson, once he arrived at Raymond, would anchor the right of this line. Raymond, incorporated in 1829, is a scenic Southern town, shaded by towering oaks among the rolling green hills of central Mississippi.3 However, in the spring of 1863, the idyllic setting was to be shattered by the approach of two belligerent armies. On May 11, McPherson's 12,000 thirsty soldiers were trudging towards Raymond from their May 10 camp at Weeks' farm, four miles past Utica along the Utica-Raymond Road. The Yanks marched only one and one-half miles on the 11th, encamping at Roach's farm on the road to Raymond. Roach's was only one-half mile from the waters of Tallahala Creek, and the parched soldiers needed water.4 On the same day, Brigadier General John Gregg's brigade of 3,000 Confederates marched into Raymond around 4:00 P.M. from Jackson.5 Confederate Sergeant Sumner Cunningham of the 41st Tennessee recalled that his regiment, upon arriving in Raymond, spent the night of May 11 in the courthouse yard, sleeping on a "fine coat of grass."6 It would be the last night on earth for some of them. McPherson's 12,000 men were rousted out of their sleep at Roach's farm at 3:30 A.M. on the morning of May 12, so that they could arrive in Raymond per Grant's order. As they were trudging through the dust from Roach's to Raymond, General Gregg was making a fateful decision for his much smaller force of 3,000. Gregg later wrote,

Captain Hall's Confederate mounted militia had trotted headlong into General McPherson's 160 man provisional cavalry battalion in the pre-dawn hours of May 12. The Yankee troopers traded shots with the butternuts, and drove them back towards Raymond, effectively screening the size of McPherson's approaching column. Hall's men galloped in a cloud of dust into Raymond, and reported to General Gregg, who recalled:

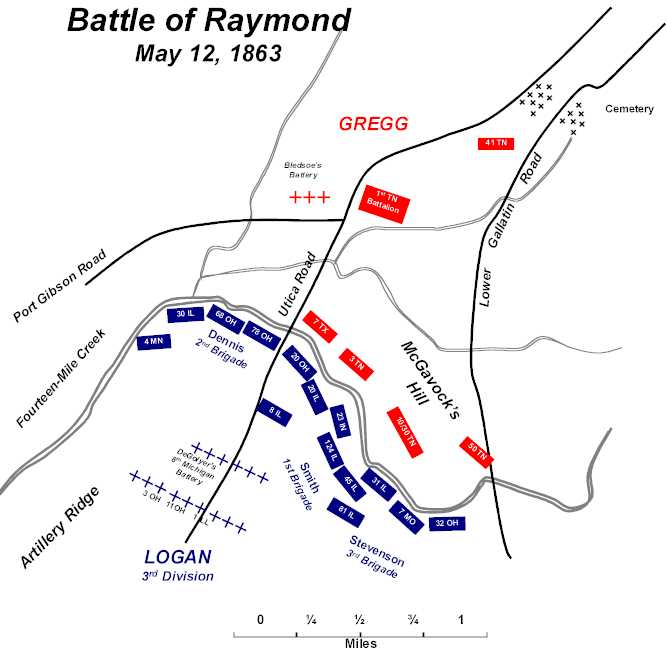

Gregg's scouts had only seen the lead brigade of McPherson's ever-lengthening column comprised of two Union divisions, hence the gross underestimate of the Yankee strength. The combative Gregg was not about to fall back, especially if he thought he was facing only a Union brigade. Ironically, he decided to set a trap for this "marauding excursion." He would lure the enemy forward on the Utica Road by placing a regiment in a blocking position where Fourteenmile Creek flowed under a wooden bridge about two miles south of Raymond. The remainder of Gregg's men would be placed in positions to support the advanced regiment, to spring the trap, and to ensure that no other Union forces were approaching on different roads. Two regiments were placed on the lower Gallatin Road, which ran almost parallel to the Utica Road and about one mile to the east. These two Tennessee regiments, at the appropriate time, were to swing westward to hit the Union right flank as the Yanks attacked the blocking position at the bridge on the Utica Road. Gregg intended to bag the perceived Union brigade. Gregg described his plan:

The trap was set--an effective trap for a large Confederate brigade of about 3,000 soldiers attacking a smaller Union brigade of about 1,500 men. However, it was a formula for an impending Confederate defeat when poor intelligence failed to identify the Union force as over 12,000 soldiers with 22 cannon. While Gregg pondered his troop dispositions, the Union infantry scuffled through the powdery Mississippi dust toward Raymond. Union Sergeant S.H.M. Byers of the 5th Iowa Infantry recorded the moment:

Because of the billowing dust caused by thousands of feet and hundreds of wheels and hooves, the interval between regiments lengthened, with soldiers using bandannas as masks against the suffocating cloud. At the head of the miles long column was the 20th Ohio Infantry Regiment, which was part of Major General John Logan's division. Ohio Sergeant Osborne Oldroyd noted in his diary, "May 12th, roused up early and before daylight marched, the 20th Ohio in the lead. Now we have the honored position, and will probably get the first taste of battle."11 Oldroyd did not record that the "honored position" also meant that his regiment stirred, rather than swallowed, the stifling dust. Oldroyd's commander, Colonel Manning Force, recalled the approach of his regiment to the enemy:

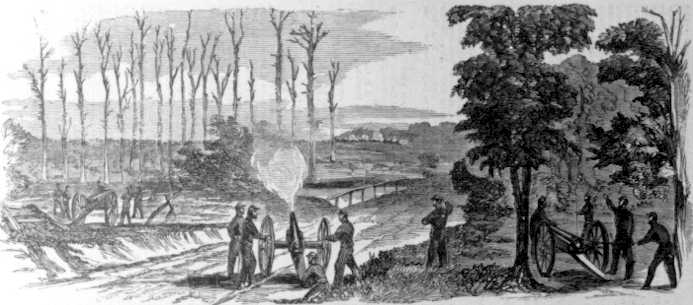

Colonel Force glanced down at his pocket watch as Captain Bledsoe's Confederate shells shrieked overhead. The time was 10:00 A.M.; the Battle of Raymond had begun with the Rebel guns forcing the issue.13 Generals McPherson and Logan were sizing up the situation when the six cannon of Captain Samuel DeGolyer's 8th Michigan Light Artillery Battery bounded up the Utica Road behind their lathering teams. DeGolyer's sweating redlegs placed their guns into battery on the left and right of the Utica Road, on a slight ridge about 400 yards south of the Fourteenmile Creek bridge.14 According to Sergeant Oldroyd, posted nearby with the 20th Ohio,

The fighting near the bridge began to intensify, and Confederate Private Cunningham remembered:

As General Gregg had ordered, the 7th Texas Infantry Regiment attacked across Fourteenmile Creek, with Colonel Hiram Granbury anchoring his regiment's right on the Utica Road and its left on the 3rd Tennessee Infantry. The 3rd Tennessee was a 500 man regiment brought forward to the creek to assist the Texans and to further bait the "trap." In support was the 41st Tennessee, brought forward from its reserve position in the town square. The Texans' attack was to be taken up by the 3rd Tennessee in a right to left movement. Private Sam Mitchell of the 3rd Tennessee recalled, General Gregg ordered Colonel Granbury to take two companies and deploy them as skirmishers, and that gallant officer was soon ready to move forward. Colonel Granbury, along with his skirmishers, soon uncovered their front and fell back and formed on the right of the brigade. The command was then given to charge! Which was done in grand style.17 Private Henry O. Dwight, with the 20th Ohio, remembers the Confederate attack:

In fact, many of the Union soldiers were not prepared for the attack. Dwight recalls what happened next:

As the Confederate attack rolled right to left, the 3rd Tennessee charged in support on the Texan's left flank. Private Frank Herron of the 3rd Tennessee recalled, "Onward we went with the rebel yell, driving the enemy back through a cornfield and across a deep narrow creek. Here we were ordered to lie down and continue to fight in this position."20 Despite the four-to-one Union odds, the Confederates obtained initial success due to the Union officers' difficulty in maneuvering their regiments into line from the corps-long column that snaked its way along the road from Utica. Private Dwight of the 20th Ohio recalled the action:

During that critical first hour of the battle, as the 20th Ohio was being flanked on its right, Private Oldroyd in the beleaguered Union regiment recalled,

General Logan's stand had bought the time needed for additional Union regiments to rush into line, and the tide of battle began to turn. Private Gouldsmith Molineaux of the 81st Illinois remembered the moment:

Meanwhile, to the east on the Gallatin Road, the two Tennessee regiments that were to be the swinging arm of Gregg's trap moved cautiously westward as ordered. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Beaumont's 50th Tennessee, the next regiment in line for the right to left attack, moved across Fourteeenmile Creek and through the belt of timber bordering the deep creek bed. Because the creek turns southeast as it approaches the Gallatin Road, Beaumont emerged from the timber south of the fighting, which was raging off first to his right, and now, his men were behind the Union right flank. From this vantage point, the bewildered officer saw a Union brigade in battle line two hundred yards to his front right, with more regiments filing into line, and at least a brigade on the ridge to his front left. Beaumont realized that the brigade he was supposed to be attacking was at least a division, and he aborted his attack. The 10th and 30th Tennessee (consolidated), which was to take up the attack upon the commitment of Beaumont's soldiers, waited for an advance that was not to come.24 This allowed the full fury of the massing Union regiments to fall upon the Texans and Tennesseans along the creek near the Utica Road. The viciousness of the battle along Fourteenmile Creek was remembered by Sergeant Ira Blanchard of the 20th Illinois Infantry Regiment:

In the smoke and dust the situation became even more confused, and General Gregg lost command and control of his scattered brigade. The Confederate regiments simply marched to the sound of the firing as the "fog of war" enveloped the battlefield. Colonel Randall McGavock of the 10th and 30th Tennessee counter-marched his soldiers from the Gallatin Road "ambush" position, then westward to the thickest of the fighting. Rushing his men to shore up the evaporating Confederate left flank, the Harvard Law School graduate and former mayor of Nashville, Tennessee, was shot dead leading a counterattack into the Union onslaught. Ironically, the 10th and 30th Tennessee was n Confederate Irish regiment, and Colonel McGavock's last charge was into the face of a Union Irish regiment, the 7th Missouri Infantry.26 Eventually, General Logan had moved his entire Third Division of McPherson's Seventeenth Corps into line of battle, and by 1:30 P.M., Brigadier General Marcellus Crocker's Seventh Division began to stream onto the contested ground.27 Simply stated, however, there was not enough space and not enough enemy for two divisions to be properly employed. Gregg's command was grossly outnumbered and his right wing was being driven back despite being reinforced by his left wing regiments. By mid afternoon, Gregg's lone brigade was in dire straits. In such situations, events usually go from bad to worse. General Gregg experienced this when one of his three cannon, a relatively rare English Whitworth breech-loading rifle, burst at the muzzle.28 Gregg eventually realized he had grossly underestimated the size of the Union force, and by 4:00 P.M. ordered his commanders to retire from the field.29 The Confederate retreat was recorded by Colonel Force of the 20th Ohio:

The Confederate view of the retreat, was, of course, despondent. Captain Flavel Barber of the 3rd Tennessee recorded:

The official, but still disputed, casualty count for the Battle of Raymond is small compared to battles such as Shiloh, Antietam, or Gettysburg--514 Confederate and 442 Union.32 The Confederate dead now lie in the Raymond City Cemetery after the citizens of Raymond moved them from their battlefield graves to the western edge of the town graveyard. After the war, the Union dead were disinterred from their resting places on Raymond's battleground and re-interred in the Vicksburg National Military Cemetery, 30 miles to the west and the site of their ultimate objective. The casualty figures belie the significance of the Battle of Raymond, which is the effect this fight had on the Vicksburg Campaign. At sundown on May 12, 1863, the victorious men of McPherson's Seventeenth Corps were policing the battlefield. The wounded of both sides were fighting for their lives in the churches, homes, courthouse, and hotel of Raymond. Major General Grant was establishing his army headquarters at Colonel Dillon's farm, seven miles west of Raymond on the Port Gibson Road.33 An excited courier rode in from Raymond to advise Grant of McPherson's victory. Grant learned that Gregg's defeated Confederates were falling back to Jackson, and his excellent intelligence reports told him that General Joseph E. Johnston and additional troops were enroute to Jackson. Grant knew that General Pemberton and a portion of the Confederate army was presently in the vicinity of Edwards, Mississippi, which was the focal point of Grant's movement on the Southern Railroad. Grant realized that Johnston would be assembling a sizeable force at Jackson. If he continued his planned move of all three Union corps to hit the railroad, he would find himself with enemy to his left front at Edwards, and to his right at Jackson. Therefore, if he continued his present course of action, his right flank would be open to attack by Johnston. If he turned his army toward Jackson, Pemberton could strike his rear. A more cautious commander would have pulled back. Instead, Grant boldly cancelled his previous movement orders toward the railroad, and at Dillon's on the night of May 12, ordered his army toward Jackson and Joe Johnston. After all, he had stolen a march on Pemberton when he moved south on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi River, then across the river into Mississippi. He had again fooled Pemberton by not marching north from Port Gibson to Vicksburg, instead turning to the northeast toward the railroad at Edwards. Now he would fool Pemberton by moving to Jackson, instead of to Edwards. Grant maneuvered his three corps into position on May 13, and on May 14 attacked and captured Jackson. He drove Johnston's men out of the capital city, and virtually destroyed the town and the railroads there. While Johnston retreated 30 miles north to Canton, Grant turned westward and attacked the unwary Pemberton at Champion Hill on May 16, driving him towards Vicksburg. He defeated Pemberton's weak blocking force at Big Black River Bridge on May 17, and bottled Pemberton in the Fortress City on May 18 and 19. After 47 days of siege operations, Grant captured fortress Vicksburg. But, just as importantly, he captured Pemberton's Army of Vicksburg. Grant understood that it was necessary to first capture the enemy forces, then the enemy territory. The Battle of Raymond looms large in history. The change in the operational situation after Raymond resulted in a change of Grant's scheme of maneuver in the Vicksburg Campaign. He boldly changed his decisive point from the Southern Railroad near Edwards to the capital city of Jackson. He made an audacious decision to attack one force at Jackson while turning his back on another at Edwards. As soon as Jackson fell, he resumed the offensive by attacking and defeating Pemberton at Champion Hill, Big Black River, and Vicksburg. Grant could never have read Clausewitz, but he innately understood that, "Reducing an enemy fortress does not amount to halting the offensive."34 The Battle of Raymond stands as a pivotal point in the most brilliant campaign ever fought on American soil. Notes: 1. Department of the Army, Operations, Army Field Manual 100-5 (Washington: U.S. Department of the Army, May, 1986), 91. 2. U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1889), Series I, Vol. 24, Part III, 297. 3. James F. Brieger, Hometown Mississippi (Jackson, MS: Town Square Books, 1980), 257. 4. Warren E. Grabau, Ninety-Eight Days--A Geographer's View of the Vicksburg Campaign (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000), 212. 5. Official Records, Series I, Vol. 24, Part I, 736. 6. White Star Consulting, "A Question of Right of Way" A Preservation and Interpretation Plan for the Raymond, Mississippi Battlefield, Preliminary Draft (Madison, AL: White Star Consulting, 1997), 10. 7. Official Records, Series I, Vol. 24, Part I, 737. 8, Ibid. 9. Ibid. 10, S.H.M. Byers, With Fire and Sword (New York: Neale Publishing Co., 1911), 68. 11. Osborne H. Oldroyd, A Soldier's Story of the Siege of Vicksburg (Springfield, IL: For the Author, 1885; reprinted by Friends of Raymond, 2001), 22. 12. Official Records, Series I, Vol. 24, Part I, 714. 13. Edwin C. Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg (Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1986), Vol. II, 49. 14. Ibid., 492. 15. Oldroyd, A Soldier's Story, 27. 16. Rebecca B. Drake, In Their Own Words: Soldiers Tell the Story of the Battle of Raymond (Raymond, MS: Friends of Raymond, 2001), 31. 17. Ibid. 31. 18. Ibid., 40. 19. Ibid., 45. 20. Ibid., 35. 21. Ibid., 45. 22. Ibid., 46, 48-49. 23. Ibid., 46. 24. Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, Vol. II, 497-498. 25. Drake, In Their Own Words, 46. 26. Bearss, The Vicksburg Campaign, Vol. II, 505. 27. Ibid., 501. 28. Warren E. Grabau, Confusion Compounded: The Pivotal Battle of Raymond, 12 May 1863 (Saline, MI: McNaughton and Gunn for the Blue and Gray Education Society, 2001), 35; Official Records, Series I, Vol. 24, Part I, 738. 29. Grabau, Ninety-Eight Days, 233. 30. Drake, In Their Own Words, 52. 31. Ibid., 56,58. 32. Official Records, Series I, Vol. 24, Part I, 6, 739; Grabau, Confusion Compounded, 66-72. 33. Bearss, The Vicksburg Campaign, Vol. II, 512. 34. Carl Von Clausewitz, On War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 599.

During his 31 years as a Regular Army and National Guard officer, he served in various command and staff positions, and founded and served as the first Commandant of the Regional Counterdrug Training Academy (R.C.T.A.) at Naval Air Station in Meridian, Mississippi. Hills retired with the rank of Brigadier General in May, 2001. He served as president of an advertising agency for 15 years in Jackson, Mississippi, and established Battle Focus upon his military retirement in 2001. He holds a bachelor's degree in Commercial Art; a Master's Degree in Educational Psychology; is a graduate of the U.S. Army War College; and is the author of A Study in Warfighting: Nathan Bedford Forrest and the Battle of Brice's Crossroads. E-Mail: parker@battlefocus.com |

||

|

| Home | Grant's March | Gregg's March | Battle of Raymond | Order of Battle | Commanders | Soldiers Who Fought | Diaries & Accounts | Copyright (c) Parker Hills, 2002. All Rights Reserved. |

Parker Hills has conducted scores of military staff rides since he organized and conducted the first

one in Mississippi in 1987. His audiences have included general officers,

commanders of various levels, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers to

include U.S. Army Special Forces (Green Berets), Army Rangers, U.S.

Marines, and British soldiers. He has traveled the nation to conduct these

staff rides, as well as to England at the request of Sandhurst Royal

Military Academy. He has also conducted dozens of civilian tours of

battlefields for non-profit organizations involved in battlefield

preservation, and is a regular speaker at Civil War Roundtables,

battlefield preservation groups, civic clubs and seminars.

Parker Hills has conducted scores of military staff rides since he organized and conducted the first

one in Mississippi in 1987. His audiences have included general officers,

commanders of various levels, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers to

include U.S. Army Special Forces (Green Berets), Army Rangers, U.S.

Marines, and British soldiers. He has traveled the nation to conduct these

staff rides, as well as to England at the request of Sandhurst Royal

Military Academy. He has also conducted dozens of civilian tours of

battlefields for non-profit organizations involved in battlefield

preservation, and is a regular speaker at Civil War Roundtables,

battlefield preservation groups, civic clubs and seminars.